[vc_row padding_top=”0px” padding_bottom=”0px” border=”none” style=”font-size: 1.2em;”][vc_column width=”1/2″][text_output]When we first traveled to Bangladesh to visit the neighboring villages of Panpara and Naya Para back in February, we were there to oversee the implementation of our cement-flooring project. We found the country to be mystifying and intriguing, the people warm and welcoming. They fed us rice and colorful curries till we were full, and then insisted we eat more, calling us sisters and brothers and uncles. Most satisfying though, was that the people we met were eager to help us help them. When we left the country, foreign in ways we could not have expected, we had the feeling we would be back soon.

We returned to the villages on a morning in late March to find saris hanging to dry long and bright in the morning sun. It was no longer “winter,” as if it ever had been. We were there on the cusp of spring when the rain would come to drown the parched land, but for now the air was heavy and still.[/text_output][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][slider animation=”slide” slide_time=”5000″ slide_speed=”650″ slideshow=”true” prev_next_nav=”true”][slide] Children spend the most amount of time on floors, therefore making them most vulnerable to parasitic infections from dirt floors.[/slide][slide]

Children spend the most amount of time on floors, therefore making them most vulnerable to parasitic infections from dirt floors.[/slide][slide] Ananya (left corner, in the blue and white polka dots) peers over the women on her porch eager to see what the commotion is all about.[/slide][slide]

Ananya (left corner, in the blue and white polka dots) peers over the women on her porch eager to see what the commotion is all about.[/slide][slide] Two girls watch as women map sanitation systems in the villages.[/slide][slide]

Two girls watch as women map sanitation systems in the villages.[/slide][slide] Women discuss the social mapping exercise.[/slide][slide]

Women discuss the social mapping exercise.[/slide][slide] A woman and her son sit outside their house in Panpara watching the social mapping taking place on their neighbor’s porch.[/slide][slide]

A woman and her son sit outside their house in Panpara watching the social mapping taking place on their neighbor’s porch.[/slide][slide] In Panpara a woman sits with her daughter and discusses life with a new cement floor.[/slide][slide]

In Panpara a woman sits with her daughter and discusses life with a new cement floor.[/slide][slide] Food lying open on a dirt floor. Situations like these can lead to parasitic and bacterial infections. Through hygiene education and modifying homes with cement floors ARCHIVE hopes to eliminate preventable illnesses.[/slide][/slider][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row padding_top=”0px” padding_bottom=”0px” border=”none” style=”font-size: 1.2em;”][vc_column width=”1/2″][slider animation=”slide” slide_time=”5000″ slide_speed=”650″ slideshow=”true” prev_next_nav=”true”][slide]

Food lying open on a dirt floor. Situations like these can lead to parasitic and bacterial infections. Through hygiene education and modifying homes with cement floors ARCHIVE hopes to eliminate preventable illnesses.[/slide][/slider][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row padding_top=”0px” padding_bottom=”0px” border=”none” style=”font-size: 1.2em;”][vc_column width=”1/2″][slider animation=”slide” slide_time=”5000″ slide_speed=”650″ slideshow=”true” prev_next_nav=”true”][slide] A new cement floor ARCHIVE, in partnership with ADESH, installed in February.[/slide][slide]

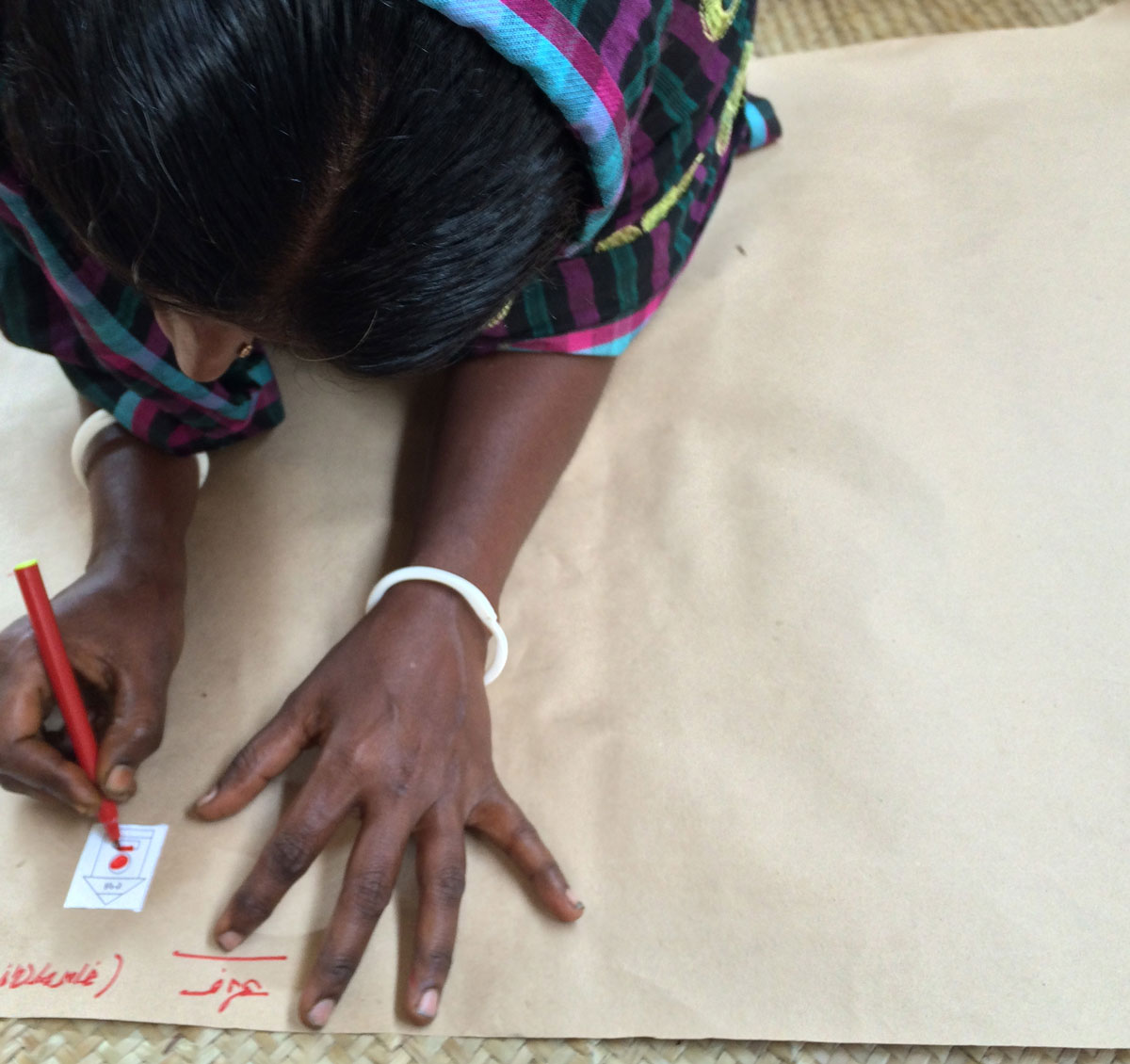

A new cement floor ARCHIVE, in partnership with ADESH, installed in February.[/slide][slide] A woman from the village of Naya Para marks a house in her village.[/slide][slide]

A woman from the village of Naya Para marks a house in her village.[/slide][slide] In Panpara, a woman sews together this tarp to create the walling for her latrine.[/slide][slide]

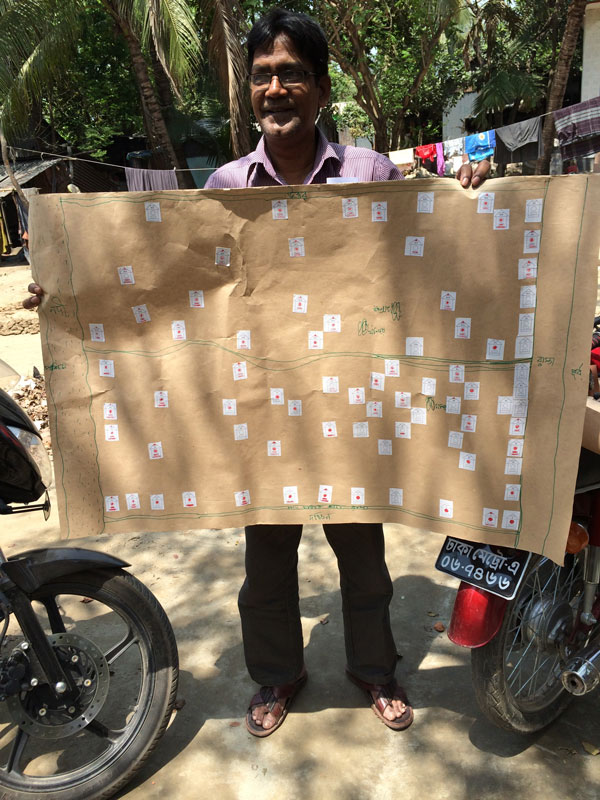

In Panpara, a woman sews together this tarp to create the walling for her latrine.[/slide][slide] A hard days work and a completed social map.[/slide][slide]

A hard days work and a completed social map.[/slide][slide] A Hindu temple in Panpara.[/slide][slide]

A Hindu temple in Panpara.[/slide][slide] An unsanitary latrine.[/slide][/slider][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][text_output]On this morning women flooded the porch of four-year-old Ananya and her family’s one bedroom house, breaking from their morning routines of washing clothes, peeling vegetables, and pumping water, while the men for the most part slept off their nighttime fishing jobs. By afternoon the children would be sleeping off heat exhaustion, but for now they peered in on the loud discussion.

An unsanitary latrine.[/slide][/slider][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][text_output]On this morning women flooded the porch of four-year-old Ananya and her family’s one bedroom house, breaking from their morning routines of washing clothes, peeling vegetables, and pumping water, while the men for the most part slept off their nighttime fishing jobs. By afternoon the children would be sleeping off heat exhaustion, but for now they peered in on the loud discussion.

What looked like a heated argument over the country’s latest bout of political unrest was instead a social mapping exercise used often by NGOs to help determine where infrastructure, in this case improved sanitation facilities, are and are not. The women marked on a map in red what was needed amongst their fellow villagers. Rotna and her family needed a latrine. Ananya’s family needed a well. Shoba and her family needed both a latrine and well in addition to a cement floor.

While our cement-flooring project can dramatically reduce parasitic infections, most notably among children under five, when we visited Panparar and Naya Para in February we could not ignore the need and the potential of improved sanitation. Improved sanitation, a toilet that keeps excreta separate from human contact, has historically been a hard find in Bangladesh. The country has made great strides in building sanitation and educating on proper practices. Yet, Bangladesh’s rich environmental context, mixed with high density, extreme poverty, and a government that seems as polluted as the river ways at times, lend to the country’s sanitation shortages. These constraints led us to be creative in our approach to providing sanitation. Our aim is that these villages can teach us how improved sanitation can be accessible in other communities worldwide. But we’re pretty sure that no community will quite compare to the home we found in Bangladesh.

-Jaclyn Hersh; External Relations Officer[/text_output][/vc_column][/vc_row]